Feedback from visitors

I’ve been most interested in the messages that viewers have taken from the exhibit. In the guest book, emails, and verbal comments, I’ve had several people say that the images had caused them to rethink their own relationship to their aging bodies.

Many women friends identified with the stereotypes of aging women thrust upon us in western culture: “Not being afraid to show our aging bodies is so positive, so thanks for doing it!! Having just had a bunch of age spots on my face zapped to remove them, I am only too aware of the negative feelings so many of us have about our natural looks.”

Some women friends commented on my vulnerability and courage to display my body in public: “I was moved by the vulnerability you opened yourself to in showing your body, with the history it carries, in this way. Such a lovely way to take all the injuries of the recent and not-so-recent past and transform them into visual poetry; a contemplation of the cycle of life: birth, growth, aging, death and regeneration.”

One friend commented that he had been upset in confronting his body through an illness a few years ago, but the exhibit helped him accept his body in a new way.

A musician friend wrote in her newsletter that the exhibit: “celebrated both life and death through photographs of hundred year old trees, highlighting Deborah’s own aging process. This truly changed my perspective.”

Others made the deeper connection and saw this as positive: “Your photos declaring our “natural” heritage and kinship came through persuasively and eloquently.”

Many found that connection most profound and beautiful in the earlier Wabi Sabi 1 exhibit with the colour image of my mother’s hands superimposed with a decaying leaf.

And there were, of course, many tree lovers: “I especially love Deborah’s notion of comparing the features of aging bodies to long lived trees! (The Standing People, as Robin Wall Kimmerer calls them in Braiding Sweetgrass!)”

I often asked visitors to choose their favourite photo or pair of photos and then photographed them in front of it. One favourite was a quite explicit reproduction of my arm trying to follow the curve of my mother’s Russian olive tree.

I loved how some offered their own bodies in comparison to the images:

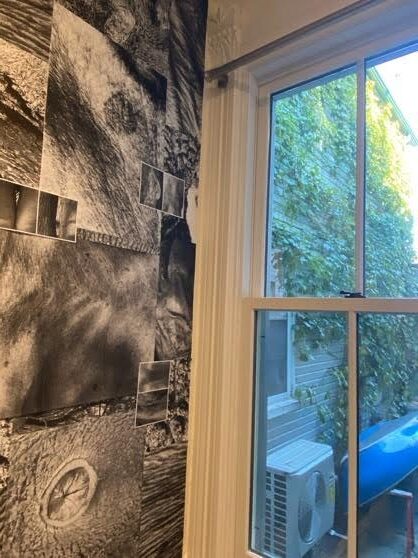

Probably the most generative piece was the collage of my test pieces – a kind of wallpaper made from the very large images and the small pairs that I first experimented with. It stimulated lots of conversation about the similarities between our bodies and trees: “It really drew me in to question and ponder. I loved that I didn’t always know whether I was looking at a tree form or a human body.”

I loved how some looked outside of the box, noticing my foot on the ceiling (an idea from gallery co-owner Leonard) and another commenting that the inside wall was complimented by the outside wall of the neighbour’s house covered with living vines.

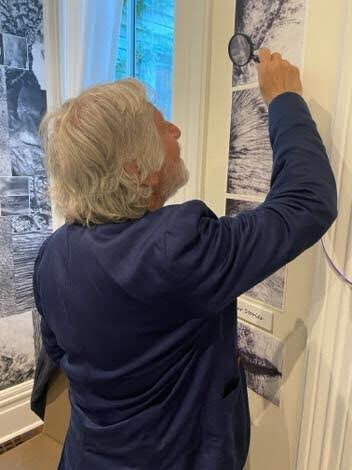

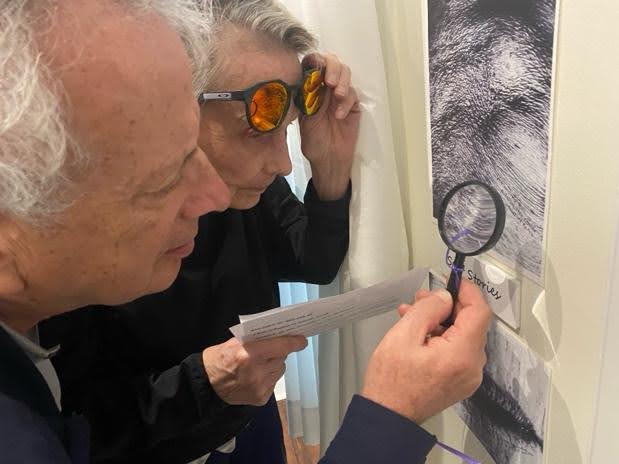

The “Scar Stories” with tiny stories scribbled on images of injuries demanded more direct engagement, sometimes using a magnifying glass.

Artist friends offered more technical feedback on the exhibit, for example, on the photos and framing: “I’m not sure why but the crisp white lines of the photo prints are visually very effective. I can’t imagine it being so successful without them.

With another artist, I had a critical discussion about the language we use to describe the later phases of our bodies. While I have wanted to claim the “beauty of decay”, she suggested that might refer more to decomposition, and perhaps in aging we “weathered” just as trees are weathered. This word recognizes the relationship with the forces and elements of life around us.

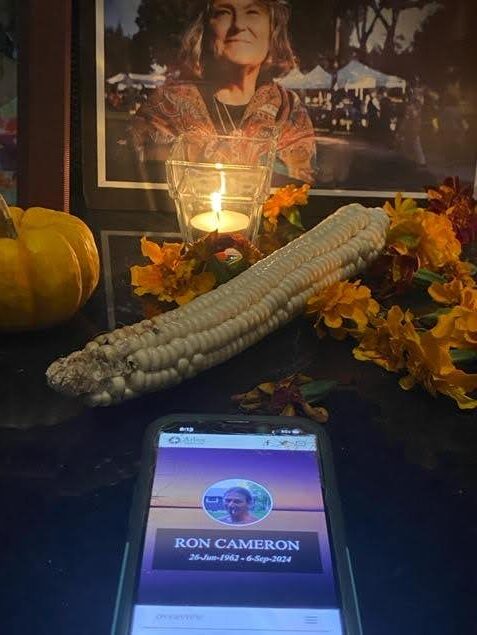

There was some participation when visitors used their cellphones to share photos: one showing me their favourite tree, another offering an image of a person to be honoured at the Day of the Dead altar.

One of my former students who assisted with the first Wabi Sabi exhibit in 2013 wrote about the whole gallery experience: “Seeing the continuation of the Wabi Sabi, hearing the joy in your singing, and how the whole afternoon just gave everyone who came a boost of love, joy, gratitude, and a time to reflect on that is vital.’

I was most moved by hearing from people I hadn’t known but who connected with the deeper motive of the project. In particular a Japanese Canadian architect who identified several ways that he saw our thinking converged:

- Wabi-sabi = in part, reclaiming lost heritage (a friend took me around Kyoto once and was humoured by my desire to see all things wabi-sabi)

- Movement based explorations (For example, I have attended some dance sessions held by those who studied under Anna Halprin and of course her husband Lawrence was one of the grandfathers of our profession)

- Native plant gardening

- Art and design (mostly art as therapy for me. My spouse is a watercolour painter)

- Decline, death and decay

- Being animal or creative creatures, speciesism and racism

- Beauty, youth and celebrity culture

This person participated in the poetry event, reading an article he had written about biophobia in our culture that eschews natural growth and wild gardens for managed landscapes.